The Legal Architecture of Apartheid – by Dr. Susan Power, Al-Haq

Introduction

Israel’s legal architecture codifies a privileged status for its Jewish citizens, and discriminates against all its non-Jewish persons, and particularly its Palestinian citizens.

Since the establishment of the State of Israel, its foundational laws provided the legal basis for Jewish domination over the Palestinian people as a whole, through entrenching their fragmentation. The State of Israel seeks to justify this discriminatory practice by claiming that Palestinians abuse their basic rights by engaging in and facilitating terrorist activity. These laws, and their associated justifications and practices, are the legal basis of Israel’s apartheid regime.

This brief serves to outline the key laws that established this regime and enabled discriminatory policies and practices to be applied to the Palestinian people as a whole.

1.Legal Framework – International Law Governing Apartheid as a Crime Against Humanity

The practice of apartheid is recognized as a crime against humanity by the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid (1976), the Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind (1996), and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998).[1] The instruments listed each identify practices and policies of racial segregation that apply systematic oppression with the purpose of establishing and maintaining the racial domination of one racial group of persons over another.

The Apartheid Convention specifically refers to measures that amount to ‘inhuman acts’, including “legislative measures… calculated to prevent a racial group or groups from participation in the political, social, economic and cultural life of the country” and “legislative measures, designed to divide the population along racial lines by the creation of separate reserves and ghettos for the members of a racial group or groups”.[2]

The Draft Code further clarifies that this crime includes “institutionalized discrimination on racial, ethnic or religious grounds”, involves the violation of fundamental human rights and freedoms and results in part of the population being seriously disadvantaged.[3] The Rome Statute, meanwhile, refers to a crime whereby unlawful conduct is committed in the context of “an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group or groups”. In addition, it clarifies that this crime is perpetrated with the specific intention of maintaining that regime.[4]

In 2011, the Russell Tribunal concluded that “Israel’s rule over the Palestinian people, wherever they reside, collectively amounts to a single integrated regime of apartheid”.[5] The conclusions were echoed by the 2019 Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), which called on Israel to eradicate policies and practices of racial segregation and apartheid that “severely and disproportionately affec[t] the Palestinian population” on both sides of the Green Line.[6]

This paper examines Israel’s discriminatory laws which form the basis of the apartheid regime imposed upon the Palestinian population as a whole, including Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line, refugees and exiles denied their right of return. These laws are codified in Knesset legislation and military orders that govern the administration of the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt).[7]

This paper maintains that the legal blueprint for Israel’s apartheid was established in 1948 and continues to the present day. It therefore adopts the conclusion of the International Law Commission, which considers apartheid to be a cumulative crime, whose breach “extends over the entire period starting with the first of the actions or omissions of the series and lasts for as long as these actions or omissions are repeated and remain not in conformity with the international obligation”.

2. Laws Providing for Jewish Supremacy and Domination

The authoritative 2017 ESCWA[8] report describes the segregation of Palestinians by Israel’s apartheid regime into a number of separate administrative, legal, and geographic ‘domains’, including Palestinian citizens of Israel; Palestinians subject to Israeli military control in the West Bank and Gaza; Palestinians in annexed and occupied East Jerusalem; and Palestinian refugees and exiles denied their right of return in the diaspora.

This strategic fragmentation has two underlying objectives: first, to prevent Palestinians from collectively mobilising to thwart Israel’s settler colonial enterprise; and second, to ensure the continuation of the settler colonial enterprise by maintaining Jewish hegemony and domination.[9]

This section outlines the laws that Israel has implemented to ensure that the Jewish population are granted peremptory recognitions of racial superiority, with the intention of maintaining Jewish dominance over the indigenous Palestinian population.

Israel’s discriminatory Law of Return (1950) grants liberal rights of immigration to Jewish persons[10] and their families. It establishes the basis that Israeli citizenship “shall be granted to every Jew who has expressed his desire to settle in Israel” and “every Jew has the right to come to this country as an oleh”.[11] The law specifically narrows the characterization of ‘oleh’ to a Jewish immigrant. Meanwhile Israel’s Nationality Law (1952) uniquely provides that, under the Law of Return, every ‘oleh’ “shall become an Israeli national”.[12]

The seven million Palestinian refugees forced from the territory during the Nakba (1948) and Naksa (1967), who have since been collectively denied their rights of return and self-determination, are notably absent from this framework. Furthermore, Israel’s Basic Law, which has a semi-constitutional status, prevents candidates perceived as a threat to the “existence of the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state” from running for elections. The law serves to silence Palestinian opposition,[13] while Israel’s Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty (1992) further entrenches “the values of the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state”.[14]

Israel’s Basic Law: the Nation State of the Jewish People (2018) provides for the outright racial superiority of the Jewish people, and sets this out as a basic principle in Article 1(a) (“The Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people, in which the State of Israel was established”). In so doing, the law implicitly erases all historical memory of the Palestinian people in historic Palestine. The Article adds that the “State of Israel is the nation State of the Jewish people” and exclusively confines the right of self-determination in the State of Israel “to the Jewish people”.[15] It also recognizes the Hebrew calendar as the official State calendar and the Hebrew language as the official State language.[16]

Article 7 of the Nation State Law establishes that the State considers the development of Jewish settlements to be a national priority.[17] In November 2020, Israel’s Krayot Magistrate’s Court cited this Article when upholding a municipal policy that denied Palestinian children access to schools in the Israeli city of Karmiel. In justification, it observed: “Karmiel is a Jewish city intended to solidify Jewish settlement in the Galilee. The establishment of an Arabic-language school or even the funding of school transportation for Arab students is liable to alter the demographic balance and damage the city’s character.”[18]

3. Citizenship and Nationality Laws

Departing from standard international practice, Israel upholds a distinction between Israeli citizenship and nationality. While the former can be acquired by i) return (for Jews only), ii) residence in Israel (e.g. Palestinians who remained in Israel immediately before the establishment of the State), and iii) birth and naturalisation[19], the latter is reserved for Jewish people alone.[20] On 11 March 2019, Prime Minister Netanyahu emphasised the distinction “Israel is not a state of all its citizens. According to the Nation-State Law that we passed, Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people – and its alone.”[21]

Israel’s apartheid practice of fragmenting the Palestinian population into separate ’domains’ is further evidenced in its racist and discriminatory application of the Entry into Israel Law (1952). When Israel issued a 1980 Basic Law that appropriated Jerusalem as its capital,[22] the UN Security Council responded with an internationally binding resolution of condemnation and non-recognition, which robustly stated that the “Basic Law on Jerusalem [is] null and void and must be rescinded forthwith”.[23] Israel then defied international opinion through its racist and discriminatory application of the 1952 Law, which imposed a temporary and revocable “permanent residency” status on Palestinian Jerusalemites that requires them to continually prove their ‘centre of life’ is in the city.[24] If they fail to do this, their residency permissions will be punitively revoked and they will be directly and forcibly transferred – at the time of writing, this fate has befallen almost 15,000 Palestinians.[25]

Former UN Special Rapporteur Richard Falk[26] describes this systematic and prolonged campaign of forced displacement as “a gradual and bureaucratic process of ethnic cleansing”[27] that, under the terms of the Apartheid Convention, amounts to a war crime,[28] crime against humanity[29] and ‘inhuman act’.[30] All of which appropriately describe Israel’s racist demographic engineering policies that seek to create a 70:30 ratio of Jews to Palestinians in Jerusalem, an objective that was clearly set out in the Jerusalem Municipality Local Outline Plan 2000.[31]

The same laws, implicitly and explicitly, subordinate the Palestinian people to the dominant Jewish population while dividing the separate Palestinian domains from each other. For example, Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip are, with minor exceptions, legally prohibited from acquiring Israeli citizenship and residing in Israel. The Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law (Temporary Provision) (2003) establishes that:

[T]he Minister of the Interior shall not grant the inhabitant of an area (the West Bank and the Gaza Strip) citizenship on the basis of the Citizenship law, and shall not give him a license to reside in Israel on the basis of the Entry into Israel Law, and the Area Commander shall not grant a said inhabitant, a permit to stay in Israel, on the basis with the security legislation in the area. [32]

Rather than granting citizenships, Israel only issues temporary permits to Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza for a cumulative period of no more than six months, which solely enable Palestinians to work or in order to seek medical treatment.[33] Through this temporary law, family unification between Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza, and their partners/family members who are Palestinian citizens of Israel or Palestinian “permanent residents” of Jerusalem, is therefore not permitted. The Law is a temporary provision that has been annually renewed since 2003 and in parallel has been extensively condemned by the Human Rights Council and CERD. Former UN Special Rapporteur, John Dugard[34] observes that the denial of family unification, in addition to other similar practices, indicates Israel’s intention to “establish and maintain domination by one racial group (Jews) over another racial group (Palestinians)”.[35]

Meanwhile, Israeli settlers illegally transferred into the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Israeli citizens are free to enter and travel throughout Israel and most of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem). A 1974 amendment to the Entry into Israel Law revokes the residencies of Palestinians who have “stayed outside Israel for a period of at least seven years” and those who have received citizenship or temporary residency in another country.[36]

A recent decision by the Pre-Trial Chamber of the International Criminal Court, which cites the Apartheid Convention and other legal sources, warns that the “arbitrary deprivation of the right to enter one’s own country” is similar to the crime against humanity of persecution. It adds that the “anguish” of persons deprived re-entry, causes “great suffering, or serious injury […] to mental […] health”.[37]

4. Law Providing for Land Appropriation

In addition to denying Palestinian nationality, Israel has implemented legislative measures for the expropriation of Palestinian lands, despite the fact that both are prohibited under Article II (d) of the Apartheid Convention. Israel’s settler colonial project has rested on the widespread and systematic confiscation of Palestinian refugee lands and property from persons classified as “absentees” or “persons who were expelled, fled, or who left the country after 29 November 1947, mainly due to the war.”[38] Their land and property was then reallocated to Jewish settlers through the newly created Development Authority.[39] The Land Acquisition Law (1953) then facilitated the Jewish settlement of lands that were not possessed by their owners and resulted in the settlement of approximately 1.2 million dunums (approximately three million acres) of Palestinian land.[40]

In parallel, Israel confiscated Palestinian lands by applying pre-existent British Mandate laws that permitted lands to be confiscated and used for public purposes by the State.[41] Israel has since amended the law to provide for State ownership of confiscated Palestinian lands, and has applied this amendment even when lands are not used for the actual public purpose described in the original confiscation order.[42]

The Legal Procedures and Implementation Law (1970) is another important part of Israel’s sweeping appropriation of Palestinian lands in occupied and annexed East Jerusalem. In the occupied West Bank, military orders are used to illegally appropriate Palestinian land as Israeli ‘State’ lands for subsequent settlement or use as archaeological zones, nature reserves and military training zones. These acts violate Articles 46, 47, 52 and 55 of the Hague Regulations (1907), Articles 33 and 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949) and are considered to be war crimes and grave breaches under the Geneva Conventions.[43]

Israeli parastatal organizations, including the Jewish Agency, the World Zionist Organization and the Jewish National Fund, facilitate the illegal inward transfer of Jewish settlers to colonize Palestinian lands, and in doing so, are chartered to carry out material discrimination against non-Jews. For example, Article 2 of the World Zionist Organization’s constitution states that “the aim of Zionism is to create for the Jewish people a home in Eretz Israel secured by public law” and explicitly advocates the settlement of the country as “an expression of practical Zionism”.[44] Israel’s Basic Law prohibits the transfer (“either by sale or in any other manner”) of lands owned by the State of Israel, the Development Authority or the Jewish National Fund; this entrenches and institutionalises the dispossession of Palestinian lands and erases the Palestinian presence from Israel’s legal framework.[45]

5. Physical Fragmentation

Israel has physically fragmented the Palestinian territory by constructing an Annexation Wall that is accompanied by a complex network of military watchtowers, checkpoints and surveillance systems that operate alongside the permit system. This cuts sections of the Palestinian community into enclaves and further enables settler colonial expansion into the West Bank.

In April 2002, the Israeli cabinet adopted a decision for the construction of a Wall that would appropriate large swathes of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, while physically separating Palestinians in Gaza, Palestinians in Jerusalem, and Palestinian citizens of Israel from the rest of the West Bank. In 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an authoritative advisory opinion, which held that the construction of the Wall and its associated regime contradict international law. It stressed that Israel has a clear obligation to bring this unlawful conduct to an end, namely by dismantling the Wall, returning land, providing compensation and giving “appropriate assurances and guarantees of non-repetition”.[46]

Israel has openly defied this Opinion and international law more generally by continuing to construct the Annexation Wall, which is currently 180 kilometers (km) long. Fifteen years after the Advisory Opinion, the Israeli cabinet approved a plan that will extend the Wall to a total length of 687 km, meaning that it will directly infringe on and harm in total 30 percent of the Palestinian population in the West Bank. Dugard and Reynolds warn that, in its aftermath, the best conceivable possible outcome will be “a Bantustan-type state in the remaining reserves”.[47]

Since 2007, Israel has completely isolated the Gaza Strip by subjecting it to a full siege and military closure, and it largely denies all Palestinian movement into and from the Strip.[48] It exerts land control through fences and military buffer zones and restricts and regulates all sea access through a naval blockade authorized by Naval Order 101. Israel also controls the entry of all goods and it uses the Defense Export Control Law (2007) and military orders to prevent “dual-use goods” from entering the territory.[49] These draconian restrictions, and their dire implications for human life in the territory, led the UN to warn, in 2012, that Gaza would be uninhabitable by 2020.[50] The pandemic now threatens to further exacerbate this ongoing humanitarian emergency.[51]

6. Laws to Prevent Palestinian Resistance

Article 2(f) of the Apartheid Convention directly refers to what it labels as an inhuman act, namely the “persecution of organizations and persons”, and “depriving them of fundamental rights and freedoms, because they oppose apartheid”.[52] In March 2017, Israel amended the Entry into Israel Law denying entry of those calling for the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment and Sanction (BDS) movement, which seeks to “challeng[e] international support for Israeli apartheid and settler colonialism”.[53] Frank La Rue, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, criticized the amendment for imposing “fresh limitations on freedom of expression in the name of national security”.[54] Meanwhile, illegally transferred Israeli settlers are granted free access into Israel and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, where they colonize new and expanding settlement blocks.[55]

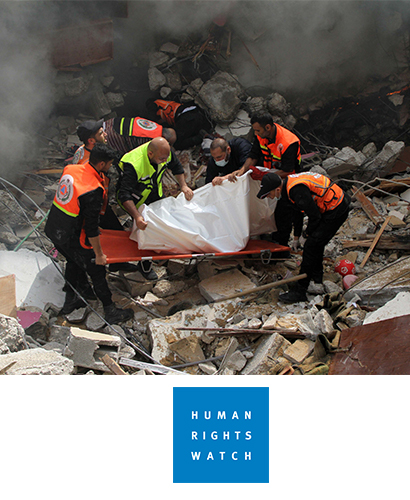

Since 1967, assemblies and gatherings in the occupied territory have been prohibited under Military Order 101. During the Great March of Return, a series of protests held at the Gaza Strip-Israel border from late March 2018 onwards, Israel operated a shoot-to-kill policy, and routinely opened fire on the assembled Palestinians, who protested peacefully their rights of return and self-determination and called for an end to the blockade. Israel’s use of unnecessary and disproportionate lethal force killed 217 Palestinians and left thousands with serious injuries, which in some cases required amputations.[56]

Israel has also implemented a number of sweeping measures that seek to prevent Palestinian parliamentarians in Jerusalem from standing for re-election in Palestine, on the pretext that their “permanent residencies” can be revoked for “breach of allegiance to the State of Israel.[57] Since 1948, in accordance with the guiding precepts of ethnic cleansing, Israel has worked to erase the Palestinian presence, including both its history and memory. Under amendment No 40 of the Budgets Law, which is also known as the “Nakba Law”, the Minister for Finance is entitled to refuse public funding to institutions that reject the existence of Israel as a “Jewish and democratic state” or that seek to commemorate “Israel’s Independence Day or the day on which the state was established as a day of mourning”.[58]

Conclusion

Israel maintains its apartheid regime through a complex framework of laws that enable demographic engineering, widespread land appropriation and the fragmentation of the Palestinian people and territory. These laws also introduce illegally transferred Jewish settlers to colonize both sides of the Green Line. Finally, racially discriminatory laws seek to subordinate the Palestinian population as a whole through denying their collective rights of return, self-determination and permanent sovereignty (over lands on both sides of the Green Line).

_________________

[1] Respectively also known as the Apartheid Convention, the Draft Code and Rome Statute. These terms will henceforth be used.

[2] Article II, International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid, G.A. res. 3068 (XXVIII)), 28 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 30) at 75, U.N. Doc. A/9030 (1974), 1015 U.N.T.S. 243, entered into force July 18, 1976 (hereafter Apartheid Convention).

[3] Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind (1996), Yearbook of the International Law Commission (1996) Volume II; Morten Bergsmo, Cheah Wui Ling, Song Tianying, Yi Ping, Historical Origins of International Criminal Law, TOAEP Volume 3, 608.

[4] Article, 7(1)(j), Elements of Crimes, p. 249, available at: https://asp.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/asp_docs/Publications/Compendium/ElementsOfCrime-ENG.pdf

[5] Russell Tribunal on Palestine, Findings of the South Africa Session (Nov. 2011), at paras 5.44 and 5.45.

[6] CERD/C/ISR/CO/17-19, Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Concluding observations on the combined seventeenth to nineteenth reports of Israel, (12 December 2019), para. 23, available at: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/ISR/INT_CERD_COC_ISR_40809_E.pdf

[7] The West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Gaza Strip

[8] United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, Israeli Practices towards the Palestinian People and the Question of Apartheid (2017) UN Doc E/ESCWA/ECRI/2017/1, available at: https://electronicintifada.net/sites/default/files/2017-03/un_apartheid_report_15_march_english_final_.pdf

[9] United Nations, ESCWA, “Israeli Practices towards the Palestinian People and the Question of Apartheid, Palestine and the Israeli Occupation, Issue No. 1” (United Nations, 2017) p. 4.

[10] Those born of a Jewish mother or who have, in some circumstances, converted to Judaism. A March 2021 ruling by Israel’s Supreme Court established that non-Orthodox converts to Judaism inside Israel may, under the Law of Return, qualify for the right to citizenship. This right already existed under the Law of Return but was reserved to converts to Judaism based abroad – see Haviv Rettig Gur, “Conversion ruling ends decades of official shunning of Reform, Conservative” Times of Israel (1 March 2021), available at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/conversion-ruling-ends-decades-of-official-shunning-of-reform-conservative/

[11] Law of Return 5710-1950 (5 July 1950), available at: https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/mfa-archive/1950-1959/pages/law%20of%20return%205710-1950.aspx

[12] Nationality Law, 5712 – 1952, available at: https://www.knesset.gov.il/review/data/eng/law/kns2_nationality_eng.pdf

[13] Article 7 (A), Basic Law: The Knesset – 1958, available at: https://www.knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/basic2_eng.htm#:~:text=Every%20Israeli%20citizen%20who%20on,to%20a%20penalty%20of%20actual

[14] Article 1, Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty, 1992 available at: https://www.knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/basic3_eng.htm#:~:text=1.,a%20Jewish%20and%20democratic%20state.&text=2.,of%20any%20person%20as%20such.

[15] Articles 1 (a)(b)(c), Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People (Unofficial translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef), available at: http://knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/basiclawnationstate.pdf

[16] Articles 4(a), 8, Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People.

[17] Adalah Position Paper, “The Illegality of Article 7 of the Jewish Nation-State Law:

Promoting Jewish Settlement as a National Value” (March 2019), available at: https://www.adalah.org/uploads/uploads/Position_Paper_on_Article_7_JNSL_28.03.19.pdf

[18] Adalah, “Israeli court relies on Jewish Nation-State Law in racist ruling: Municipal funding of school busing not required for Arab kids as it would encourage Arab families to move into ‘Jewish city’” (30 November 2020), available at: https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/10191

[19] Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Acquisition of Israeli Nationality (1 January 2010), available at: https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/aboutisrael/state/pages/acquisition%20of%20israeli%20nationality.aspx#:~:text=The%20Law%20of%20Return%20(1950,a%20member%20of%20another%20religion.

[20] Article 1(b), Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State Of The Jewish People, available at: https://knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/BasicLawNationState.pdf

[21] Jonathan Ofir, “Netanyahu tells the truth: ‘Israel is not a state of all its citizens’” Mondoweiss (11 March 2019), available at: https://mondoweiss.net/2019/03/netanyahu-israel-citizens/

[22] Israel unlawfully annexed Jerusalem, the capital of Palestine, in 1967; also see Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, available at: https://www.knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/basic10_eng.htm

[23] UNSC/RES/478 (1980).

[24] Article 1(b), Entry into Israel Law, 5712 – 1952, available at: http://www.hamoked.org/files/2011/2240_eng.pdf

[25] 14,683 Palestinians

[26] Former UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967.

[27] A/HRC/25/67, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, Richard Falk (13 January 2014) p. 11, para. 34

[28] ICC Statute, Article 8(2)(b)(viii)

[29] ICC Statute, Article 7(1)(d)

[30] Article II(c), Apartheid Convention; Hamoked, Ministry of Interior Data: 40 East Jerusalem Palestinians were stripped of their permanent residency status in 2019 as part of Israel’s ‘quiet deportation’ policy; a significant increase compared to 2018 (28 June 2020) Last visited (21.11.2020) http://www.hamoked.org/Document.aspx?dID=Updates2174

[31] Municipality of Jerusalem, Jerusalem Outline Plan – No. 2000, available at: https://www.jerusalem.muni.il/en/residents/planningandbuilding/cityplanning/masterplan/;Changing the Demographics of Jerusalem, (13 December 2017) available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/75006 https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/75006; section 7 “Demographic Balance “According to Governmental Decisions” – This goal, as presented by the municipality and adopted in governmental discussions regarding the matter, seeks to maintain a ratio of 70% Jews and 30% Arabs. The population forecast, like forecasts prepared in other frameworks, indicates that this goal is not attainable and that demographic trends in place since the end of the 1960s distance Jerusalem from the set goal. It can be assumed, very probably, that if the demographic trend of recent years continues without any significant change, the situation in 2020 will be a population of approximately 60% Jews and 40% Arabs, and this is only under the condition that assumptions at the base of the outline plan are actualized.”

[32] The Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law (temporary provision) 5763 – 2003, available at: https://www.knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/citizenship_law.htm

[33] The Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law (temporary provision) 5763 – 2003

[34] Former UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967.

[35] Agenda Item: Item7: Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories, 28th Regular Session (2015 Mar), Resolution adopted by the Human Rights Council

28/27; CERD/C/65/Dec.2, ICERD, Prevention of racial discrimination, including early warning measures and urgent action procedures, Decision 2 (65) Israel (10 December 2004); Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, UN Doc. A/HRC/4/17, 29 Jan. 2007, para. 50.

[36] Article 11(a), Entry into Israel Regulations, 5734-1974, available at: http://www.hamoked.org/files/2018/3050_eng.pdf

[37] ICC-RoC46(3)-01/18, Decision on the “Prosecution’s Request for a Ruling on Jurisdiction under Article 19(3) of the Statute”, Pre-Trial Chamber I, p. 44, para. 77,

[38] Article 1(b)(1), Absentees’ Property Law, 5710-1950, available at: https://unispal.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/0/E0B719E95E3B494885256F9A005AB90A; Adalah, “Absentees’ Property Law”, available at: https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/538

[39] Article 19(a) of the Absentees’ Property Law, 1950, provides that “it shall be lawful for the Custodian to sell the property to that Development Authority”.

[40] Land Acquisition (Validation of Acts and Compensation) Law (1953). See Adalah to Attorney General and Custodian of Absentee Property: Israel’s Sale of Palestinian, Last visited (21.11.2020) https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/7003

[41] Land Acquisition for Public Purposes Ordinance, 1943.

[42] Land (Acquisition for Public Purposes) Ordinance – Amendment No. 10.

[43] Question of Palestine: Legal Aspects (Doc. 4) – DPR publication (New York, 1992), available at: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-199200/

[44] The Constitution of the World Zionist Organization and the Regulations for its Implementation (Updated November 2019), available at: https://www.wzo.org.il/files/pages/item/thumbsrc/WZO_Constitution_amended_Nov_2019.pdf

[45] Basic Law: Israel Lands (1960).

[46] Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion (9 July 2004) Para. 142 – 153, available at: https://www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/131/131-20040709-ADV-01-00-EN.pdf

[47] OCHA, The Wall Report, (2019), available at: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-200240/; John Dugard, John Reynolds, “Apartheid, International Law, and the Occupied Palestinian Territory” EJIL 24 (2013), 867, 900.

[48] Entry to Israel Order (Exemption of Gaza Strip residents) (2005); Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law (Temporary Order) (2003).

[49] Defense Export Control Order (Controlled Dual-Use Goods Transferred to Areas under Palestinian Civilian Control) (2008).

[50] Gisha, Controlled Dual Use Items, available at: https://gisha.org/UserFiles/File/LegalDocuments/procedures/merchandise/170_2_EN.pdf; UNRWA, Gaza In 2020, A Livable Place? (August 2012) Last visited (24.11.2020) https://www.unrwa.org/userfiles/file/publications/gaza/Gaza%20in%202020.pdf

[51] Al-Haq, “In the face of potential COVID-19 outbreak in the Gaza Strip, Israel is obliged to take measures to save lives” (7 April 2020), available at: https://www.alhaq.org/advocacy/16694.html; Al-Jazeera, “Israel blocks shipment of Russian Sputnik V vaccine to Gaza” (16 February 2021), available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/16/palestinians-say-israel-blocking-shipment-of-vaccines-to-gaza

[52] Article 2(f), UN General Assembly, International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid, 30 November 1973, A/RES/3068(XXVIII), available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3c00.html

[53] BDS, “What is BDS?”, available at: https://bdsmovement.net/pt/what-is-bds

[54] BDS, “What is BDS?” available at: https://bdsmovement.net/what-is-bds; United Nations, The Question of Palestine, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression (A/HRC/41/35/Add.2) (Excerpts) para 47, available at: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/report-of-the-special-rapporteur-on-the-promotion-and-protection-of-the-right-to-freedom-of-opinion-and-expression-a-hrc-41-35-add-2-excerpts/

[55] UN News, “Israel: ‘Halt and reverse’ new settlement construction – UN chief” (19 January 2021), available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/01/1082482

[56] Gaza 2020 (9 June 2020) Last visited (24.11.2020) https://medium.com/@lifttheclosure/its-2020-lift-the-gaza-closure-c3f586611c11

[57] Al-Haq, “Urgent Appeal: Israel Must Suspend and Repeal Recent Legislation Allowing for the Revocation of Permanent Residency Status from Palestinians in Jerusalem for ‘Breach of Allegiance’” (18 March 2018), available at: https://www.alhaq.org/advocacy/6262.html

[58] “Nakba Law” – Amendment No. 40 to the Budgets Foundations Law, 2011, available at: https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/496

Dr. Susan Power

Dr. Susan Power (BCL, National University of Ireland, Galway, PhD, Trinity College Dublin) is Head of Legal Research and Advocacy at Al-Haq, Law in the Service of Man. She lectured law for seven years in Griffith College Cork and Dublin, Ireland between 2010 and 2017. Dr. Power has worked on the Control of Economic Activities in Occupied Territories Bill (Ireland 2018), submitted communications to the International Law Commission on the Draft Principles on the Protection of the Environment in Relation to Armed Conflicts, worked on communications and amicus curiae submissions to the International Criminal Court, presented on the Zero Draft Treaty for an Internationally Binding Treaty on Business and Human Rights and presented to the Catalan parliament on violations of international law in the occupied Palestinian territory. She has published academic articles in the Journal of Conflict and Security Law, Irish Yearbook of International Law and the Irish Journal of European Law, writing on issues of occupation law, amongst others and has been a Committee member and judge on the Irish Red Cross International Humanitarian Law Moot Court, Corn Adomnáin.

Al-Haq is an independent Palestinian non-governmental human rights organisation based in Ramallah, West Bank. Established in 1979 to protect and promote human rights and the rule of law in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), the organisation has special consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council.

Al-Haq documents violations of the individual and collective rights of Palestinians in the OPT, irrespective of the identity of the perpetrator, and seeks to end such breaches by way of advocacy before national and international mechanisms and by holding the violators accountable. The organisation conducts research; prepares reports, studies and interventions on breaches of international human rights and humanitarian law in the OPT; and undertakes advocacy before local, regional and international bodies. Al-Haq also cooperates with Palestinian civil society organisations and governmental institutions in order to ensure that international human rights standards are reflected in Palestinian law and policies. The organisation has a specialised international law library for the use of its staff and the local community.

Al-Haq is the West Bank affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists – Geneva and is a member of the International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR-Net), the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network (EMHRN), the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Habitat International Coalition (HIC), the Palestinian Human Rights Organisations Council (PRHOC), and the Palestinian NGO Network (PNGO).

For its work in protecting and promoting human rights, the organisation has been awarded the Fayez A. Sayegh Memorial Award, the Rothko Chapel Award for Commitment to Truth and Freedom, The Carter-Menil Human Rights Foundation Prize, the Geuzenpenning Prize for Human Rights Defenders, the Welfare Association’s NGO Achievement Award, The Danish PL Foundation Human Rights Award, the Human Rights Prize of the French Republic, the Human Rights and Business Award, and the 2020 Gynne Skinner Award for corporate accountability.