Palestinians in East Jerusalem – Richard Falk and Virginia Q Tilley, Israeli Practices towards the Palestinian People and the Question of Apartheid. UNESCWA

Palestinians in East Jerusalem

Richard Falk and Virginia Q Tilley, Israeli Practices towards the Palestinian People and the Question of Apartheid. Beirut: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for East Asia (UNESCWA)

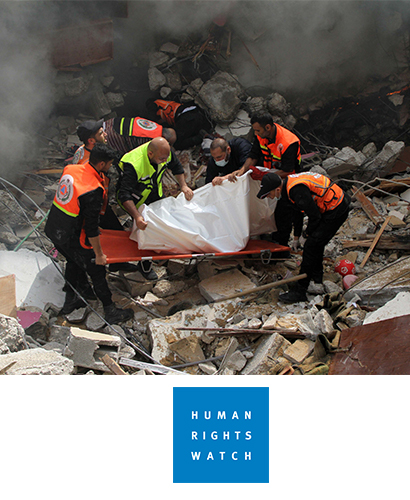

Israeli policies towards the some 300,000 Palestinians in East Jerusalem can be addressed more concisely.[1] The discrimination evident in domain 1 is reproduced: Palestinians in East Jerusalem experience discrimination in areas such as education, health care, employment, residency and building rights, experience expulsion from their homes and house demolitions consistent with a project of ethnic engineering of Greater Jerusalem, and suffer harsher treatment at the hands of the security forces.[2]

The central question here, however, is not whether Israel discriminates against Palestinians — amply confirmed by the data — but how the domain for Palestinians in East Jerusalem operates as an integral element of the apartheid regime. In brief, domain 2 situates Jerusalem Palestinians in a separate category designed to prevent them from adding to the demographic, political and electoral weight of Palestinians inside Israel. Specific policies regarding their communities and rights are designed to pressure them to emigrate and to quell, or at least minimize, resistance to that pressure. The “grand apartheid”[3] dimension of this domain can be appreciated by observing how the Israeli Jerusalem municipality has openly pursued a policy of “demographic balance” in East Jerusalem. For instance, the Jerusalem 2000 master plan seeks to achieve a 60/40 demographic balance in favour of Jewish residents.[4] As long ago as the 1980s, the municipality had drafted master plans to fragment Palestinian neighbourhoods with intervening Jewish ones, stifling the natural growth of the Palestinian population and pressuring Palestinians to leave.[5]Describing Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem as “neighbourhoods” is part of the wider tactic of disguising violations of international humanitarian law through the use of non-committal language.

Such policies have a significant impact because Jerusalem has such importance for the collective identity of Palestinians as a people. For them, the city is the administrative, cultural, business and political capital of Palestine, home to the Palestinian elite, and site of hallowed places of worship and remembrance. Although many Palestinians in East Jerusalem maintain networks of family and business connections with Palestinian citizens in Israel, the West Bank and (now to a lesser extent) the Gaza Strip, their primary interest is to go about their lives and pursue their interests in the city where they have homes, businesses, a vigorous urban society, strong cultural resonances, and, in some cases, ancestral roots going back millennia.

Israel pursues efforts to weaken the Palestinians politically and contain their demographic weight in several ways. One is to grant Palestinians in East Jerusalem the status of permanent residents: that is, as foreigners for whom residency in the land of their birth is a privilege rather than a right, subject to revocation. That status is then made conditional on what Israeli law terms their “centre of life”, evaluated by documented criteria such as home and business ownership, attendance at local schools and involvement in local organizations. If the centre of life of an individual or family appears to have shifted elsewhere, such as across the Green Line, their residency in Jerusalem may be revoked. A Palestinian resident of Jerusalem who has spent time abroad may also find that Israel has revoked his or her residency in Jerusalem.

Proving that Jerusalem is one’s “centre of life” is burdensome: it requires submitting numerous documents, “including such items as home ownership papers or a rent contract, various bills (water, electricity, municipal taxes), salary slips, proof of receiving medical care in the city, certification of children’s school registration”.[6] The difficulty in meeting the criteria is suggested by the consequences of failure to do so: between 1996 (a year after the “centre of life” legislation was passed) and 2014, Jerusalem residency was revoked for more than 11,000 Palestinians.[7] To avoid that risk, a growing, albeit relatively low, number of Palestinians are seeking Israeli citizenship. Israel has granted only about half of those requests.[8]

Their fragile status as permanent residents leaves Palestinians in East Jerusalem with no legal standing to contest the laws of the State or to join Palestinian citizens of Israel in any legislative challenge to the discrimination imposed on them. Openly identifying with Palestinians in the occupied Palestinian territory politically carries with it the risk of Israel expelling them, for violating security provisions, to the West Bank and removing their right even to visit Jerusalem. Thus, the urban epicentre of Palestinian nationalism and political life is caught inside a legal bubble that neutralizes Palestinians’ capacity to oppose the apartheid regime.[9]

______________

[1] The figure of 300,000 was provided by the Association for Civil Rights in Israel in March 2015.

[2] For more details, see A/HRC/31/73; B’Tselem, “Statistics on Palestinians in custody of the Israeli security forces (January 2017, available from http://www.btselem.org/statistics/detainees_and_prisoners); Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Humanitarian Bulletin (16 November 2015, available from https://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_the_humanitarian_monitor_2014_12_11_english.pdf); Alternative Information Center (AIC), “OCHA: One in two Palestinians to need humanitarian assistance in 2017” (26 January 2017, available from http://alternativenews.org/index.php/headlines/329-ocha-one-in-two-palestinians-to-need-humanitarian-assistance-in-2017).

[3] See Tilley, A Palestinian declaration.

[4] A/HRC/22/63, para. 25.

[5] For further discussion of the Jerusalem master plans, see Francesco Chiodelli, The Jerusalem Master Plan: planning into the conflict, Journal of Palestine Studies, No. 51 (Ramallah: Institute of Palestinian Studies, 2012). Available from www.palestine-studies.org/jq/fulltext/78505. For related maps, see Bimkom, Trapped by Planning: Israeli Policy, Planning and Development in the Palestinian Neighborhoods of East Jerusalem (Jerusalem, 2014). Available from http://bimkom.org/eng/wp-content/uploads/TrappedbyPlanning.pdf.

[6] B’tselem, “Revocation of residency in East Jerusalem”, 18 August 2013. Available from www.btselem.org/jerusalem/revocation_of_residency.

[7] Data from B’tselem, Statistics on Revocation of Residency in East Jerusalem. Available from www.btselem.org/jerusalem/revocation_statistics.

[8] Maayan Lubell, “Breaking taboo, East Jerusalem Palestinians seek Israeli citizenship in East Jerusalem”, Haaretz, 5 August 2015. Available from www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.669643. According to the article, the number of Jerusalem Palestinians applying for Israeli citizenship has grown to between 800 and 1,000 annually, although in 2012 and 2013 only 189 out of 1,434 applications were approved.

[9] Nonetheless, Palestinians in Jerusalem have made formidable contributions to critiques of Israeli policies, the more impressive for their having done so under such conditions.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA)

This report was commissioned by the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) from authors Mr. Richard Falk and Ms. Virginia Tilley.

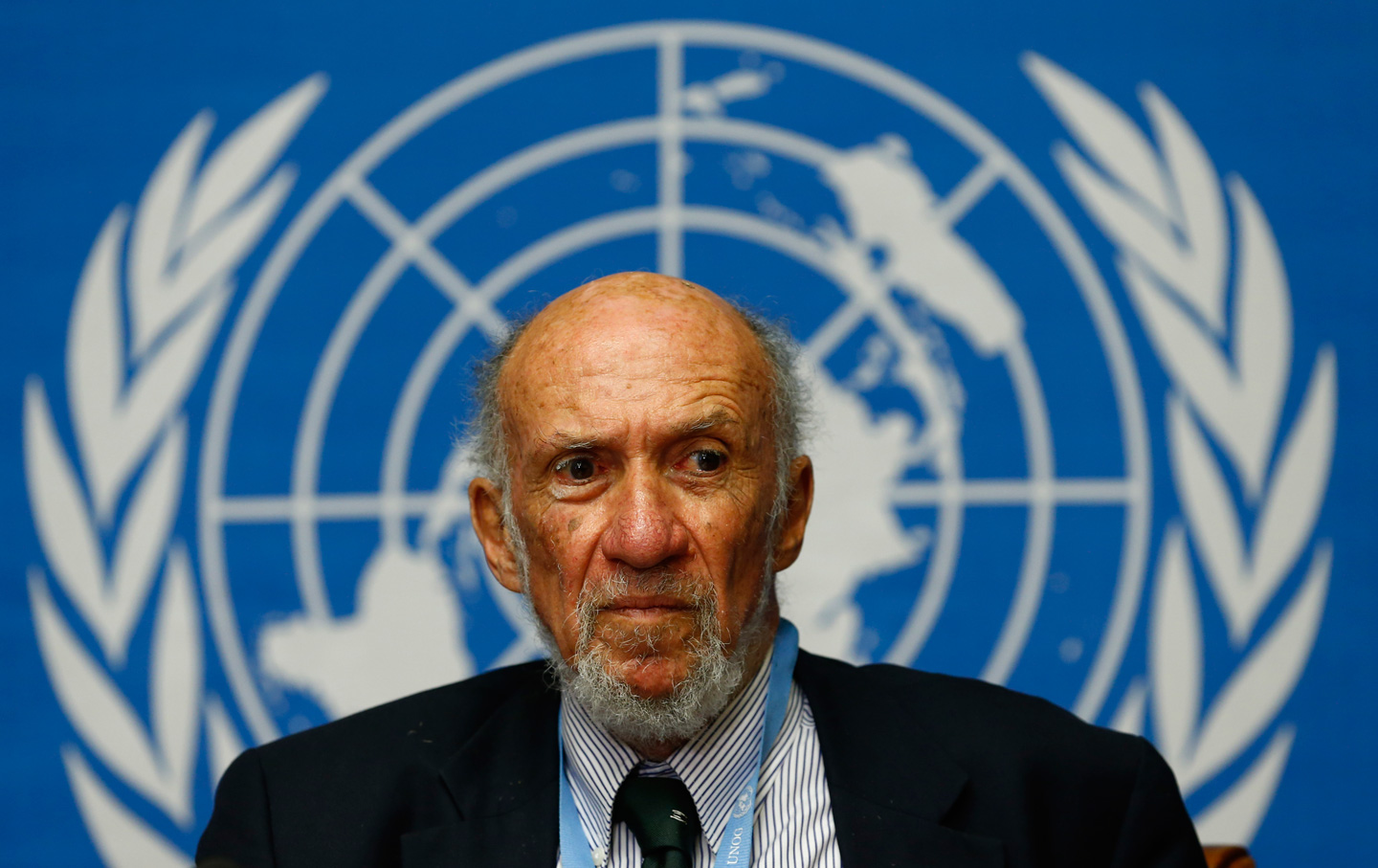

Dr. Richard Falk

Richard Falk is currently Research Fellow, Orfalea Center of Global and International Studies, University of California at Santa Barbara, and Albert G. Milbank Professor of International Law and Practice Emeritus at Princeton University. From 2008 through 2014, he served as United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967. He is author or editor of some 60 books and hundreds of articles on international human rights law, Middle East politics, environmental justice, and other fields concerning human rights and international relations.

Dr. Virginia Tilley

Virginia Tilley is Professor of Political Science at Southern Illinois University. From 2006 to 2011, she served as Chief Research Specialist in the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa and from 2007 to 2010 led the Council’s Middle East Project, which undertook a two-year study of apartheid in the occupied Palestinian territories. In addition to many articles on the politics and ideologies of the conflict in Israel-Palestine, she is author of The One State Solution (University of Michigan Press and Manchester University Press, 2005) and edit of Beyond Occupation: Apartheid, Colonialism and International Law in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (Pluto Press, 2012).