Economic sanctions are a time-honored feature of international relations governed by international law. Generally, a sanction in international law is a threatened penalty or punishment for disobeying a law or other established rule. The purpose of sanctions can be synonymous with terms such as deterrent, punition, disciplinary action, penalization, coercively corrective measure, retribution, and may take the form of an embargo, a ban, prohibition, boycott, barrier, restriction, or tariff.

More specifically, economic sanctions considered here are measures taken by a state, or states, and their corresponding organs to coerce another state to conform to an international agreement or norm of conduct, typically in the form of restrictions on trade, access to finance, or other goods and services. The analyst’s first critical test is to determine if the sanctions align with the aforementioned purposes and objectives shared among the imposing states.

A sanction may apply in multiple forms, ending military cooperation, degrading diplomatic relations and withholding recognition, as well as cultural, sports and/or academic boycotts. These manifestations of international sanction also may bring about significant moral and/or material, direct and/or indirect consequences; however, these measures are ancillary to the subject of this chapter.

The purposes and degrees of sanctions may vary in their application, whether as a tool of political pressure, as an alternative to exacting enforcement or judicial action, or other coercive measure. This chapter reviews ETOs in the narrower context of economic sanctions, although the analyst may apply the parameters, exercises and tests proffered here to a wider range of sanctions in practice. The scope of economic sanctions also may range widely from international, as exercised by the UN Security Council (SC) or General Assembly (GA), as in the case of anti-apartheid boycott, divestment and sanction (BDS). Alternatively, the actual source and practice of economic sanctions could be regional in scope and/or unilateral in their application. Regardless of their scope, economic sanctions are subject to the same examination to determine their alignment with internationally lawful purposes.

The SC sanctions regimes have become well institutionalized, diversified and targeted through more than 50 years of operation. In doing so, the SC has grounded effective measures in the domestic, individual, collective and extraterritorial obligations of states under international law, humanitarian law, criminal law and peremptory norms of customary international law, including the duty of nonrecognition of an illegal situation created by the illegal use of force or other serious breaches of jus cogens.[1] Legal and judicial mechanisms no less than the International Law Commission and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) have reaffirmed these obligations of states, dating back to the "Namibia Doctrine,” whereby the ICJ advised that the

development of international law in regard to non-self-governing territories, as enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations, made the principle of self-determination applicable to all of them” and that "the termination of the Mandate and the declaration of the illegality of South Africa’s presence in Namibia are opposable to all States in the sense of barring erga omnes the legality of a situation which is maintained in violation of international law…

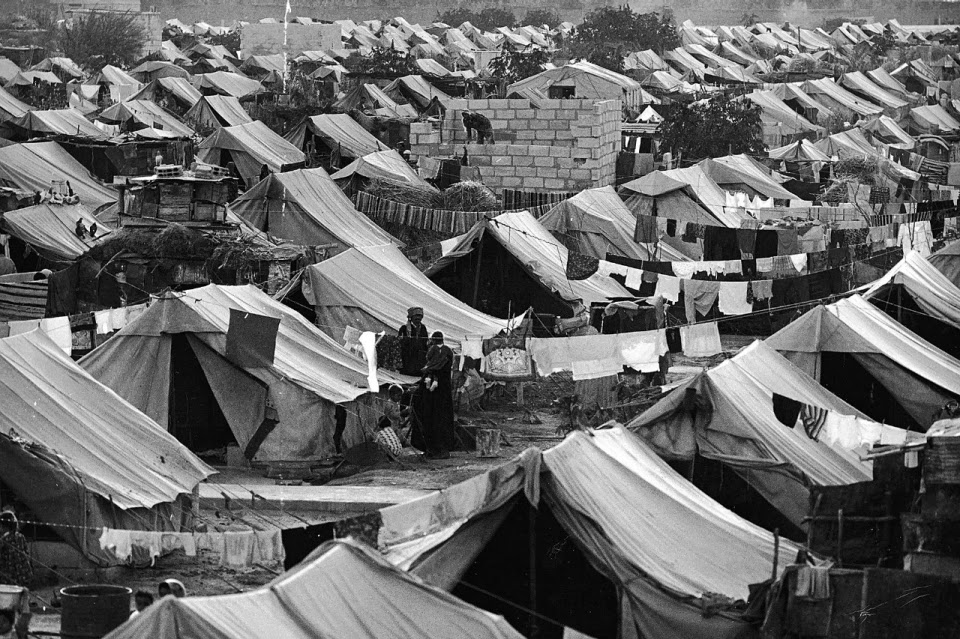

In the case of the enduring conflict in Palestine, the United Nations bears a "permanent responsibility towards the question of Palestine until the question is resolved in all its aspects in a satisfactory manner in accordance with international legitimacy.”[2] Despite the UN’s overarching responsibility to uphold Palestinian self-determination, international law and world order, 75 years of failure to uphold the UN Charter in this case have undermined the faith of generations in the rule of law, cost untold fortunes and persecuted an entire people. Within this greater problematic is the inconsistency of the SC, in its present veto-bound form, to respond with effective measures to remedy the ongoing crimes of population transfer, institutionalized material discrimination (apartheid) against Palestine’s indigenous people, the foundational breach of uti possidetis iuris (the international law principle prohibiting partition and recolonization of a people’s territory/self-determination unit)[3] and the litany of gross violations of human rights. Despite its prominence in the international agenda and current events, Palestine is not the only example of its kind, but shares many features with the double standards affecting human rights of the peoples of Kashmir, Kurdistan, Nagaland, Tibet, West Papua, Western Sahara, Xinjian/East Turkestan and other indigenous peoples. All of the influential states committing grave breaches and gross violations of human rights in these regions since the UN’s founding have escaped SC actions called for under Chapter VII.

By way of example, many observers—and the actual voting record—have shown that the principal obstacle to the SC applying effective remedies to the illegality brought about by Israel is the United States of America’s veto privilege.[4] Only once, in 1980, did the SC succeed to "[call] upon all States not to provide Israel with any assistance to be used specifically in connexion with [its illegal] settlements in the occupied territories.”[5] However, that SC action was not accompanied by a mandatory sanction regime, monitoring Committee of Experts or other mechanism to enforce the grave breach of IHL[6] and serious crime of population transfer,[7] in this case.

Two years later, the UNGA also reminded UN Member states of the illegality of recognizing or cooperating with the illegal situation in Palestine when it condemned the annexation of Palestinian territory by Israel and further deplored "any political, economic, financial, military and technological support to Israel that encourages Israel to commit acts of aggression and to consolidate and perpetuate its occupation and annexation of occupied Arab territories…”[8] In doing so, the GA has reiterated its call to "all Member States” to apply specific measures to:

- refrain from supplying Israel with any weapons and related equipment and to suspend any military assistance that Israel receives from them;

- refrain from acquiring any weapons or military equipment from Israel;

- suspend economic, financial and technological assistance to, and cooperation with Israel;

- sever diplomatic, trade and cultural relations with Israel…[9]

Thus, the UN retained an institutional memory of prior legal obligations that the ICJ also cited in its own 2004 Advisory Opinion on the construction of a wall in the occupied Palestinian territory, reiterating that the illegal situation has resulted in "an obligation not to render aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by such construction.” The ICJ reminded that, in the context of war and occupation, The Hague Convention and the four Geneva Conventions "incorporate obligations essentially of an erga omnes character”[10]; that is, binding on all.

The duty of nonrecognition, noncooperation or nontransaction with parties to the illegal situation is self-executing in the sense that such erga omnes requirements are axiomatic and do not require specific SC resolutions for states to exercise this extraterritorial obligation. However, the SC is specially mandated to articulate, monitor and operationalize these obligations as the UN body with "primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security.” Nonetheless, the SC’s actions and inactions in maintaining universal standards in the conduct of sanctions are not immune to the test of institutional and legal integrity that a researcher or analyst brings to the field of authoritative opinion.

[1] Stefan Talmon, "The Duty Not to ‘Recognize as Lawful’ a Situation Created by the Illegal Use of Force or Other Serious Breaches of a Jus Cogens Obligation: An Obligation without Real Substance?” in Christian Tomuschat and Jean-Marc Thouvenin, eds., The Fundamental Rules of the International Legal Order. Jus Cogens and Obligations Erga Omnes (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff, 2005), at: http://users.ox.ac.uk/~sann2029/6.%20Talmon%2099-126.pdf; Enrico Milano, "The doctrine(s) of non-recognition: theoretical underpinnings and policy implications in dealing with de facto regimes,” at: http://www.esil-sedi.eu/fichiers/en/Agora_Milano_060.pdf; Werner Meng, "Stimson Doctrine,” in Rudolf Bernhardt, ed., Encyclopedia of Public International Law, Vol., No. IV (1982), 690; and David Turns, "The Stimson Doctrine of Non-Recognition: Its Historical Genesis and Influence on Contemporary International Law,” Chinese Journal of International Law, Vol. 2, No. 1 (2003), at: 105–43; Marcel Kohen, "La contribución de América Latina al desarrollo progresivo del Derecho Internacional en materia territorial,” Anuario de derecho internacional. XVII, 57–78, at: http://dadun.unav.edu/bitstream/10171/22094/1/ADI_XVII_2001_04.pdf; Martin Dawidowicz, "The Obligation of Non-recognition of an Unlawful Situation,” in James Crawford, Alain Pellet and Simon Olleson, eds., The Law of International Responsibility (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), at: http://www.lalive.ch/data/publications/OUP_Chapter_(2010).pdf.

[2] "Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People,” A/RES/70/12, 2 December 2015, at: https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/UNISPAL.NSF/47D4E277B48D9D3685256DDC00612265/F2EA91B32BB0309985257F11005E27FA.

[3] Marcelo G, Kohen, "La contribution de l’Amérique latine au développement progressif du droit international en matière territorial,” Relations internationals, n° 137 (2009/1), pp. 13–29 https://www.cairn.info/revue-relations-internationales-2009-1-page-13.htm.

[4] Donald Neff, "An Updated List of Vetoes Cast by the United States to Shield Israel from Criticism by the U.N. Security Council,” Washington Report of Middle East Affairs (May/June 2005), p. 14, at: http://www.wrmea.org/2005-may-june/an-updated-list-of-vetoes-cast-by-the-united-states-to-shield-israel-from-criticism-by-the-u.n.-security-council.html; "U.N. Security Council: U.S. Vetoes of Resolutions Critical to Israel (1972–Present),” Jewish Virtual Library (2011), at: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/UN/usvetoes.html; Nick Bryant, "US raises prospect of Israel UN isolation,” BBC News (1 April 2015), at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-32117501.

[5] S/RES/465 (1980), 1 March 1980, para. 7, at:

https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/5AA254A1C8F8B1CB852560E50075D7D5.

[6] As "transfer of civilian population in to occupied territory” is prohibited in Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilians in Time of War of 12 August 1949.

[7] As previously prosecuted at the International Military Tribunals at Nuremberg and Tokyo, 1945–46. "The human rights dimensions of population transfer, including the implantation of settlers,” E/CN.4/Sub.2/1993/17, 6 July 1993, at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f4194.html.

[8] General Assembly, "The situation in the Middle East,” A/37/123 (1982), 16 December 1982, at:

http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/37/a37r123.htm.

[9] Ibid., para. 13.

[10] ICJ, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, General List 131, 9 July 2004, at: http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/84/6949.pdfhttp://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/131/1671.pdf.