Apartheid Briefs

Current Apartheid Issues Explained

Apartheid Briefs

The ugly record of Israel’s crimes against Palestinians continues unabated for 73 years. Unlike any settler-colonial project, the settlers would not only seize the land and evict the people but they apply their policy and practice to eliminate the people from the land, history and geography. To this, Israeli settlers added the unique feature that the settlers pose as the REAL people of the land in a unique imposter position never seen in any colonial project. The imposters appropriate the people’s food, dress, customs and place names. It was a desperate attempt to portray East European Poles and Russians as the natural people of Palestine, like their kith and kin, the Syrians and the Egyptians.

Palestinians fight for survival in their homeland for over a century, and literally in the last 73 years or 26,000 days to measure the daily suffering. Unarmed by weapons, they are armed by the unbeatable weapon: the Right to Return Home.

How did this come about?

Since the Al-Quds/Al-Aqsa Intifada broke out in October 2000, thousands of Palestinian citizens of Israel (PCI) have been directly affected by violence and murders. In the last two decades, no less than 1,400 PCI have been killed and more than 5,000 injured. The increase in violence has become the biggest challenge that confronts this group and it has pushed aside, even if only temporarily, the struggle against racial discrimination and for equality, including the abolition of the country’s racist laws.

Nelson Mandela was born in 1918: the First world war was coming to an end, the British occupation of Palestine had begun and the global pandemic known as the ‘Spanish Flu’ was about to devastate many countries. Mandela was born in the state of South Africa, which at that time was less than ten years old. In many ways he was born into interstitial space, as what had been four separate British colonies were still amalgamating into one administration (the Union of South Africa) and segregationist policies for the control of ‘native affairs’ were still being developed out of those inherited from the British colonisers. Growing up in deep rural Eastern Cape, Mandela inherited what was very much a colonial milieu.

He moved to Johannesburg in 1941 and began cutting his political teeth in the African National Congress (ANC) at precisely the moment it was being radicalised by a new generation of younger leaders; this was also the dawn of South Africa’s apartheid era, which formally began in 1948 when the National Party won the general election of that year. The party used the term ‘apartheid’ as an election slogan: while over time substitute appellations were used by the party and State, ‘apartheid’ stuck as the term of choice world-wide for a system of governance (and a legitimising ideology) that endured in its essentials until 1994. Mandela’s political journey, and his life path, were henceforth defined by the struggle against apartheid.

In chronological terms, South African struggles have therefore paralleled Palestinian struggles. Although they had a very different history and occurred in entirely separate contexts, there was nonetheless a powerful solidarity between them.

The conflation of anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism is, at first glance, a relatively recent innovation that has deeply troubling implications for freedom of speech and political discourse. In this week’s contribution, the academic Joseph Massad provides important insight by placing this conflation in historical context and demonstrating that it has actually been a feature of Zionism since its inception. Crucially, he highlights how the ‘founding fathers’ of the Israeli state recognised anti-Zionism as an instrument they could use to advance their political goals, and thereby demonstrates how anti-Semites and Zionists found a common cause in the establishment of the Israeli state.

Historical research has established for many decades that European Christians and Jews were native European converts to the two Palestinian religions of Christianity and Judaism, and were not descendants of their ancient adherents, any more than today’s Indonesian or Chinese or Bosnian Muslims are descendants of the ancient Arab Muslims of the Arabian Peninsula. But given the force of European racialism and Europe’s deeply racist culture, both then and now, the belief in the foreignness of Jews persisted. It is a belief that the Zionist movement espoused.

It is well-documented that Israel systematically discriminates against non-Jews, and Palestinians in particular. This, after all, is a country where its prime minister, Benyamin Netanyahu, openly boasted that ‘Israel is not a state of all its citizens. According to the basic nationality law we passed, Israel is the nation state of the Jewish people – and only it’.

This raises the question of whether this racism is a recent phenomenon or if it was instead embedded in the original thinking of the founding Zionist leaders. This brief tries to answer this question by going back to the origins of the Zionist project and examining how it intersected with colonialism and race theories in the late 19th century. In asserting that Zionism is indeed inherently (both in theory and practice) racist, it draws attention to its clear desire to dispossess, dominate and persecute Palestine’s indigenous population.

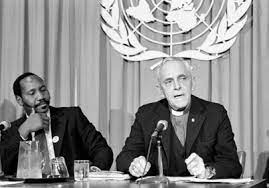

International solidarity with South Africans struggling against apartheid and international isolation of the apartheid state both formed a crucial pillar in the country’s struggle for liberation and democracy. The Anti-Apartheid Movement eventually became the largest solidarity movement in the world and the largest civil society campaign of the twentieth century, with structures or activities in most countries. It operated alongside a range of actions by – mostly Global South – governments and intergovernmental organisations. This brief examines the role of the United Nations, and its Special Committee Against Apartheid in particular, in this struggle.

Part I considers the Committee’s role in the period 1962-1975. Part II of this brief, which will be published next week, considers the Committee’s contribution in the period between the Soweto massacre of 1976 and the country’s first democratic elections in 1994. It concludes with valuable insights and recommendations that relate to the Palestinian struggle.

Israeli policies towards the some 300,000 Palestinians in East Jerusalem can be addressed more concisely. The discrimination evident in domain 1 is reproduced: Palestinians in East Jerusalem experience discrimination in areas such as education, health care, employment, residency and building rights, experience expulsion from their homes and house demolitions consistent with a project of ethnic engineering of Greater Jerusalem, and suffer harsher treatment at the hands of the security forces.

The central question here, however, is not whether Israel discriminates against Palestinians — amply confirmed by the data — but how the domain for Palestinians in East Jerusalemoperates as an integral element of the apartheid regime.

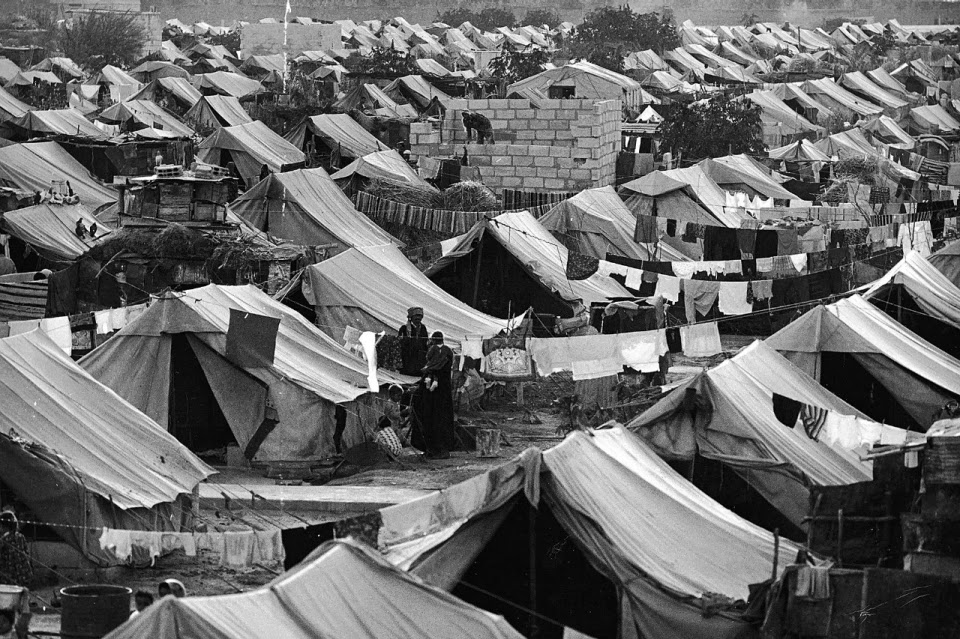

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly approved Partition Resolution No 181, and thereby endorsed an arrangement that would split Palestine into Jewish (55 percent) and Arab (44 percent) states and place Jerusalem (1 percent) under a special status of corpus seperatum (‘separated body’).

Somewhat perversely, the number of Arabs (528,000) in the proposed ‘Jewish’ State exceeded the number of Jews (449,000), and this was clearly something of concern for Zionists who viewed a Jewish majority as the necessary precondition of a Jewish state. Far from resolving the problem, the Resolution therefore raised the prospect of further conflict. As Ilan Pappé observes, “when an ideology of exclusivity is adopted in a highly charged ethnic reality, there can be only one result: ethnic cleansing”. And Zionist leaders duly demonstrated this when they applied a plan that drove Palestinians off their land, creating a nation of refugees in the process.

The newly established State of Israel then turned its attention to pillaging Palestinian properties.

It is almost unheard of for a functioning democracy to fail to uphold equality before the law, as this is not just morally indefensible but also violates universal values and principles. This is clearly recognised by Article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which stipulates that “[a]ll are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law”.

Israel’s legal architecture codifies a privileged status for its Jewish citizens, and discriminates against all its non-Jewish persons, and particularly its Palestinian citizens.

Since the establishment of the State of Israel, its foundational laws provided the legal basis for Jewish domination over the Palestinian people as a whole, through entrenching their fragmentation. The State of Israel seeks to justify this discriminatory practice by claiming that Palestinians abuse their basic rights by engaging in and facilitating terrorist activity. These laws, and their associated justifications and practices, are the legal basis of Israel’s apartheid regime.

This brief serves to outline the key laws that established this regime and enabled discriminatory policies and practices to be applied to the Palestinian people as a whole.