Settler Colonialism, Apartheid and Rising Violence Among Palestinians in Israel – by Prof. As’ad Ghanem

Settler Colonialism, Apartheid and Rising Violence Among Palestinians in Israel

Internal Palestinian Violence: A Comprehensive Phenomenon

Since the Al-Quds/Al-Aqsa Intifada broke out in October 2000, thousands of Palestinian citizens of Israel (PCI) have been directly affected by violence and murders. In the last two decades, no less than 1,400 PCI have been killed and more than 5,000 injured[1]. The increase in violence has become the biggest challenge that confronts this group and it has pushed aside, even if only temporarily, the struggle against racial discrimination and for equality, including the abolition of the country’s racist laws.[2]

Opinion polls conducted in 2018-2019 demonstrate that the majority of PCI view this internal violence as the most important political issue that needs to be addressed.[3] Although criminal gangs are in large part responsible for this violence, and murder cases in particular, it is quite clear that the issue is ‘comprehensive’ because it is broad-ranging, both in terms of its causes and implications for all PCI. It is therefore urgent and pertinent to engage with this phenomenon, and to propose possible treatments that will ‘normalise’ the situation and stem the manifestations and spread of violence.[4]

Recent reports indicate that the rate of violence in Palestinian society in Israel (PSI) has increased rapidly over the last two decades. Arabs account for approximately two-thirds of all victims of violence in the country, despite only accounting for about 18 percent of the total population (the murder figures are similar); 82 percent of those suspected of possessing illegal weapons are Arabs; and half of the country’s prisoners are Arab.[5]

Dr. Badi Hasisi, a specialist in this field from the Hebrew University, observes:

[N]o day goes by without hearing about a shooting or murder in the Arab society, so that the data show that the percentage of Arab citizens who are killed is three times more than their percentage in the general population and that there are 12 times more shootings in the Arab community than in the Jewish community in Israel.[6]

In this brief essay I argue that although there are several reasons behind the growing internal violence among the PSI, the major and main one is the state structure and policies. My main argument is that the ‘state superstructure’ is key to understanding ‘internal’ violence within the PSI.

Settler-colonialism, the apartheid system and the exacerbation of social violence

Opinions about the sources and causes of the violence in PSI vary and cite various factors, including poverty, social change, clan and inter-generational clashes and gang violence.[7] In addition, most scholars focus on single causes, which reflects and produces the misconception that there is only one factor that affects violence.[8] While this is certainly the case in particular cases, this clearly negates the possibility of a complete and/or comprehensive account. If a comprehensive account is to be worked towards and achieved, then it is a precondition to consider the interaction and collision between different factors. In other words, it is not possible to talk about violence without considering the political, social, cultural and psychological factors that constitute the general framework that dominates and affects PCI.

Any such analysis must also acknowledge the main structure of the State and the ways in which it deals with the country’s indigenous people. I therefore propose to begin with a description of the State of Israel (SoI) and its foundations, structure and systems and, in considering its relation to Palestinian citizens, emphasize its impact on Palestinian society in general, and the spread of violence in particular. I will also acknowledge and engage secondary factors such as globalization, social changes and economic conditions.

In a recent report (June 30, 2021) Moshe Nesbaum, a Channel 12 television correspondent, reported on a meeting of senior police officials that was attended by Omer Bar-Lev, Israel’s minister of internal security. Nesbaum reported that one participant claimed that” most of the criminals – Arabs – who carry out serious crimes in Arab society work as agents of the Shin Bet – the General Security Service. [T]he police cannot pursue them because they have immunity from the Shabaq [security services]”[9] This is consistent with one of the axioms of clandestine security work – namely that while employers know of their work, they do not forbid their actions, or even provide permission in the first instance.

This full acknowledgment of the existence of a close relationship between the Shin Bet, which has significant influence on the SOI’s policies towards the Palestinians in Israel, and crime in PSI serves to confirm that a purely internal analysis, which focuses on internal cultural, economic and social changes, is not sufficient. It is also, by implication, necessary to focus on targeted policies that seek to drive the fragmentation and exclusion of PCI, and to register how they seek to engender internal conflicts between Palestinian society’s organs and individuals with the aim of preventing Palestinians from addressing societal contradictions and struggling against an apartheid system that enshrines and upholds racial segregation and discrimination.

In his book Arabs in the Jewish State,[10] the American political scientist Ian Lustick examines the policies that Israel applied in the first three decades after its establishment, which continue to guide the SoI’s policy towards its Palestinian citizens. He shows how these policies, which were applied in the Nakba and then extended to the rest of Palestine after the 1967 War,[11] seek to complete the Zionist project of taking over Palestine, dispersing its indigenous people and restricting their ability to exert their collective power.

A framework for understanding the violence and its intensification: the role and significance of the state

In order to understand the relationship between settler colonialism and internal Palestinian violence, it is essential to review the basic literature on this subject. Both Wolfe and Veracini[12] explain the meaning of the term by referring to its practices and methods, such as the weakening and dispersing of the indigenous community. In recent years, studies have shown a close relationship between settler-colonialist practices in Israel and the situation of Palestinian society, both inside and outside the ‘Green Line’[13]. These studies focus on policies of exclusion and neglect and an ethnically-defined system of segregation, and explain how they are key to understanding the rampant violence in PSI.

Israel is the product of two historical developments that continue to influence its dealings with the Palestinians, both inside and outside the ‘Green Line’. First, the establishment of the SoI was the result of an ongoing process of colonization that seeks to separate and alienate the native people from their land and their country and replace them with Jews or non-Jews.[14] Second, Israel was formed, and continues to develop, on the basis of an apartheid regime that enshrines the principle of ethnic superiority and seeks to uphold Jewish superiority in Israel. This was confirmed by the passing of the “Nation-State” law in 2018 in addition to a series of new discriminatory laws and regulations.[15]

The Nakba was a seminal moment, in terms of its immediate consequences, repercussions and implications, and it continues to impact Palestinians to this day. Since its establishment, the SoI has discriminated against and oppressed Palestinians. The SoI was declared to be a Jewish state and aspired to become the state for the Jewish people, which would achieve the goals of the Jews and serve their interests.[16] Palestinians who became citizens after 1948 were subject to a system of control and official State policies that continue to enshrine their inferior status and restrict their individual and collective rights.[17]

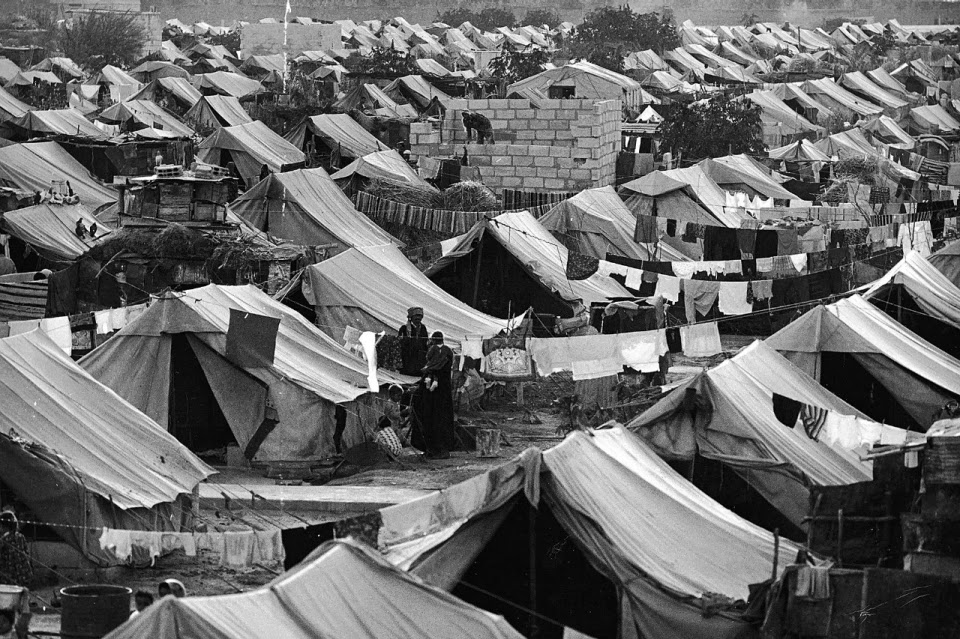

The Palestinian Arab population who were uprooted in the war of 1948 and in subsequent years, were mostly prevented from returning to their original villages. The Judaization of the Galilee, Triangle and Naqab regions, along with related policies of exclusion and discrimination, further exacerbated the problems of the PCI, which included the emergence of a truncated social order, increasing poverty, a lack of access to geographical space, housing overpopulation and the emergence of communities that resembled refugee camps, with low basic services, high unemployment and low-level job opportunities[18]. All of these objective triggers generated internal crises and conflicts over space and limited resources, and further exacerbated violence.

Government control policies impeded the strengthening of local Palestinian national capacities, and obstructed the development of appropriate remedial methods that could be addressed to the cultural, political and social challenges that confront

PCI.[19] While other factors, such as social structure, cultural beliefs, the status of women and economic conditions are important,[20] the State superstructure is clearly the most important factor in the modern era.

The State’s policies towards its Palestinian citizens upholds the superior rights of a particular ethnic groups and shows a preference for this group in most socio-economic domains, and this serves to underline that the security and lives of Jewish Israelis are privileged. This principle is manifested and reiterated every day. For example, it is obvious that no Israeli security officer or policeman/woman will put him/herself at risk to protect a non-Jew, and this is clearly related to the State’s failure to respond to violent acts in Palestinian society, and the increased incidence of violence among PCI. For example Dr. Nohad Ali, a specialist in violence and crime issues, observes that

[C]rime in the Arab community in Israel does not occupy a high place in the national priorities of the State of Israel, the police and the other law enforcement agencies. There is a culture of disregarding crime as long as it occurs within Arab society, in addition to a culture of non-cooperation [by Arabs] with the police and the refusal to file complaints against relatives and neighbors , as there is mistrust between Arab society, law enforcement agencies and the police.[21]

Since the establishment of the SoI, Israeli police have viewed Palestinians as a national security threat,[22] and this is shown by the limited police engagement with Arab towns and willingness to address criminal incidents. Also, no serious work has been done to combat violence in PSI, or to ensure the personal safety of Palestinian citizens.[23]

Ali Haider, a lawyer, notes:

“[T]he most important reasons for the spread of violence include political violence practiced by the state, that is, the violence of the state, which monopolizes the use of means of force and uses advanced techniques to achieve this. The political violence of the state is represented in the policies of the government, the enactment of laws that give the Jewish citizen a higher rank, statements and restatements of fascist positions, physical attacks on Palestinian citizens and public and holy places, in addition to the demolition of hundreds of homes, and the demolition of entire villages, time after time. Actions and policies towards the unrecognized villages in the Naqab, provide clear evidence of a violent state policy”[24]

Conclusion

In discussing violence in PSI, we should acknowledge several internal factors that cut across cultural, economic, political and social dimensions. In this article I have however suggested that the crucial factor is actually external to the PSI, and have therefore emphasized State policies applied in the name of a Jewish majority that considers the State to be its exclusive property.

Israel is the product of a colonization process, and this feature continues to influence crucial aspects of its contemporary policies. The “system of apartheid”, whose very existence has been increasingly acknowledged by the scientific literature and public opinion, is also crucial. Both underpin the policies applied by the Israeli State, to Palestinians in general, and PCI in particular, with the intention of undermining their ability to collectively resist.

We can therefore understand ‘internal’ violence within the PSI by referring back to the Balfour Declaration, the associated policies of the British Mandate, the Nakba, the drafting and implementation of the UN “partition plan” and the flight, expulsion and dispossession of most of the Palestinian population (and subsequent prevention of their return), which Pappé has described as ‘ethnic cleansing.[25] The State’s discrimination against ‘its’ Palestinian citizens has been built on these foundations, along with a deliberate and conscious attempt to create divides between them and oPt and diaspora Palestinians.

Restriction, exclusion and discrimination have therefore been accompanied by the cultivation of an ambiguous Palestinian relationship with the State, and this has established a material basis for the weakening and disintegration of the PCI.[26] Dozens of research projects and studies have also described how government-directed policies have tried to deepen divisions within Palestinian society and spread violence and crime. For example, the previously mentioned Moshe Nesbaum report directly blamed the Shin Bet and the police for the spread of violence within the PSI.[27] However, any analysis of this phenomenon must take colonialism and racial supremacy into account, and recognize that apartheid targets the community and the lives of indigenous people in order to weaken them and create internal division. In doing so, it seeks to prevent them from confronting state policies in effective ways.

_____________________

[1] Ali, Nohad, Ruth Lewin-Chen, and Ola Najami-Yousef, Violence, crime and policing in Arab society: Personal and community security index – 2019. (Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research and Abraham Initiatives: 2020). [in Hebrew and Arabic].

[2] I intend to focus on the ‘social’ level and internal conflicts and give limited consideration to legal issues, questions and themes

[3] See: Ali, Nohad, Ruth Lewin-Chen, and Ola Najami-Yousef, Violence, crime and policing in Arab society: Personal and community security index – 2019. (Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research and Abraham Initiatives: 2020). [in Hebrew and Arabic].

[4] My intention is not to simply describe the phenomenon and its spread, as this information is already freely available on several Internet sites, and is referenced in various academic articles and reports.

[5] See: Benita, R. Data on severe violence in the non-Jewish sector. )Report of the Knesset Research and Information Center, 2018). [In Hebrew]. https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/Info/mmm/pages/document.aspx?docid=cas-65110-j8p4c6

[6]See : https://www.haaretz.co.il/debate/1.7965060

[7] Ali, Nohad, Ruth Lewin-Chen, and Ola Najami-Yousef, Violence, crime and policing in Arab society: Personal and community security index – 2019. (Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research and Abraham Initiatives: 2020). [in Hebrew and Arabic].

[8] See: Barak, Gregg. Violence and nonviolence: Pathways to understanding. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003); Dekeseredy, Walter and Barbara Perry (Eds.). Advancing critical criminology: Theory and application. (NY. Lexington Books, 2003); Gottfredson, Michael, and Travis Hirschi. A general theory of crime. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1990); Oliver, William. The violence social world of black men. (NY: Lexington Books, 1994).

[9] See https://www.mako.co.il/news-law/2021_q2/Article-921fce655fd5a71026.htm in hebrew

[10] Lustick, Ian, Arabs in the Jewish State: Israel’s control of a National Minority. (Austin: Texas University Press: 1980).

[11] See: Ghanem, As’ad and Muhannad Mustafa. Palestinians in Israel. (Madar: Ramallah, 2008). And Pappe, Ilan. The biggest prison on earth: A history of the occupied territories. (London: Oneworld Publications: 2020).

[12] Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, 4 (2006): pp. 387-409; Veracini, Lorenzo. Israel and Settler Society. (London: Pluto Press, 2006); Veracini, Lorenzo, 2014. “Understanding colonialism and settler colonialism as distinct formations.” Interventions 16 (5):615-633; Veracini, Lorenzo. “Introducing settler colonial studies.” Settler Colonial Studies 1 (2011):1-12; Veracini, Lorenzo. The settler colonial present. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). Vol. 23 No. 1. Pp. 45-59; Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, 4 (2006): 387-409.

[13] See for example: Ghanem, As’ad and Muhannad Mustafa, 2008. Palestinians in Israel. (Madar: Ramallah, 2006) [In Arabic]; Ghanem, As’ad. “The deal of the century in context – Trump’s plan is part of a long-standing settler-colonial enterprise in Palestine.” Arab World Geographer Vol 23, no 13 (2020) 45-59; Khalidi, Rashid. The hundred years’ war on Palestine: A history of settler colonialism and resistance, 1917-2017. (London: Profile Books, 2020); Pappé, Ilan. The biggest prison on earth: A history of the occupied territories. (London: Oneworld Publications: 2020); Rouhana, Nadim. “Decolonization as reconciliation: Rethinking the national conflict paradigm in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41:4 (2018), 643-662, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1324999 ; Rouhana, Nadim and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury. “Memory and the return of history in a settler-colonial context: The case of the Palestinians in Israel”, Interventions, 21:4 (2019): 527-550, DOI: 10.1080/1369801X.2018.1558102 ; Rouhana , Nadim & Areej Sabbagh-Khoury. “Memory and the Return of History in a Settler-colonial Context: The Case of the Palestinians in Israel.” Interventions, 21:4 (2019), 527-550, DOI: 10.1080/1369801X.2018.1558102 ; Yiftachel, Oren and As’ad Ghanem. “Understanding ‘ethnocratic’ regimes: the politics of seizing contested territories,” Political Geography, Volume 23, Issue 6, (August 2004), Pages 647-676.

[14] See: Ghanem, As’ad and Muhannad Mustafa. “The Palestinians in Israel: The Challenge of the Indigenous Group Politics in the ‘Jewish State’ “. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs Vol. 31 No.2. (2011), pp. 177-196.

[15] For details see Adalah report: https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/7771 and Ghanem, As’ad and Khatib, Ibrahim. The nationalisation of the Israeli ethnocratic regime and the Palestinian minority’s shrinking citizenship. Citizenship Studies, 21:8 (2017), 889-902.

[16] See: Ghanem, As’ad and Muhannad Mustafa. Palestinians in Israel – The policies of the indigenous minority in the ethnic state. (MADAR, Ramallah 2009).

[17] See Lustick, Ian (1980). Arabs in the Jewish State: Israel’s control of a National Minority. Austin: Texas University Press; Pappe, Ilan. The Forgotten Palestinians: A History of the Palestinians in Israel. (Yale University Press, 2013).

[18] See Zureik, Elia. The Palestinians in Israel: A study in internal colonialism. (Routledge, 1979); Pappe, Ilan. The Forgotten Palestinians: A History of the Palestinians in Israel. (Yale University Press, 2013).

[19] See Rouhana, Nadim and As’ad Ghanem. “The crisis of minorities in ethnic states: The case of the Palestinian citizens in Israel,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 30:3 (1998), 321-346.

[20] See the strategic plan of the High Follow-up Committee on Palestinian Issues in Israel on combating violence, which I supervised (A.G.). High Follow-up Committee. Towards a strategic project to combat violence and crime in Arab society. (Nazareth: Higher Follow-up Committee, 2019).

[21] Ali, Nihad. Civil terrorism – Violence and crime in Arab society. (Haifa: University of Haifa, 2014), pp. 37-38, 60, 72

[22] Ghanem, As’ad and Ibrahim Khatib. The nationalisation of the Israeli ethnocratic regime and the Palestinian minority’s shrinking citizenship. Citizenship Studies, 21:8 (2017), 889-902.

[23] Ali, Nihad. Civil terrorism – Violence and crime in Arab society. (2014) pp 37-38 .

[24] Lawyer Ali Haidar. On violence, Al- Madar (2012) website https://www.almadar.co.il/news-11,N-31251.html [in Arabic]

[25] Pappe, Ilan. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2006)

[26] See analysis by: Rouhana, Nadim & As’ad Ghanem. “The crisis of minorities in ethnic states: The case of the Palestinian citizens in Israel,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 30:3 (1998), 321-346.

[27] See https://www.mako.co.il/news-law/2021_q2/Article-921fce655fd5a71026.htm [in hebrew]

As'ad Ghanem

As’ad Ghanem (PhD) is a leading academic and intellectual among the Palestinians in Israel, currently a lecturer at the School of Political Science, University of Haifa.

His theoretical work has explored the legal, institutional and political conditions in ethnic states and conflict studies. He published 14 books and numerous articles about ethnic politics in divided societies, including about ethnic divisions and Arab-Jewish relations in Israel. He has covered issues such as Palestinian political orientations, the establishment and political structure of the Palestinian Authority, and majority-minority politics in a comparative perspective. His books include Palestinian Politics after Arafat: A Failed National Movement (Indiana Series in Middle East Studies). Ghanem has initiated several empowerment programs for Palestinians in Israel.