Nelson Mandela, Palestinian Struggles and Decolonisation – by Prof Verne Harris

Nelson Mandela, Palestinian Struggles and Decolonisation

Nelson Mandela was born in 1918: the First world war was coming to an end, the British occupation of Palestine had begun and the global pandemic known as the ‘Spanish Flu’ was about to devastate many countries. Mandela was born in the state of South Africa, which at that time was less than ten years old. In many ways he was born into interstitial space, as what had been four separate British colonies were still amalgamating into one administration (the Union of South Africa) and segregationist policies for the control of ‘native affairs’ were still being developed out of those inherited from the British colonisers. Growing up in deep rural Eastern Cape, Mandela inherited what was very much a colonial milieu.

He moved to Johannesburg in 1941 and began cutting his political teeth in the African National Congress (ANC) at precisely the moment it was being radicalised by a new generation of younger leaders; this was also the dawn of South Africa’s apartheid era, which formally began in 1948 when the National Party won the general election of that year. The party used the term ‘apartheid’ as an election slogan: while over time substitute appellations were used by the party and State, ‘apartheid’ stuck as the term of choice world-wide for a system of governance (and a legitimising ideology) that endured in its essentials until 1994. Mandela’s political journey, and his life path, were henceforth defined by the struggle against apartheid.

In chronological terms, South African struggles have therefore paralleled Palestinian struggles. Although they had a very different history and occurred in entirely separate contexts, there was nonetheless a powerful solidarity between them.

Mahmood Mamdani has argued that South Africa’s apartheid state and the state of Israel are best understood as ‘settler-colonial nation-states’, where members of the chosen nation enjoy full citizenship and indigenous peoples and formations are made into permanent minorities.[i] The colonial logic of ‘native reserves’ and its apartheid counterpart (and its corollaries of ‘separate development’ and ‘self-determination’) use the chimera of sovereignty to mask exclusion and minoritisation. In both South Africa and Israel, the trappings of a modern democratic state completely fail to hide the fundamental attributes of a colonial polity. South African and Palestinian struggles for freedom are, for this reason, quintessentially decolonisation struggles.

Periodisation almost always gives rise to difficulties, and this also applies to efforts to cast the period 1948-1994 as South Africa’s ‘apartheid era’.[ii] First, apartheid patterns in South African society are proving extremely resilient, meaning that apartheid only formally ended in 1994 . Second, the system’s roots stretch back to a colonialism inaugurated in the seventeenth century that the post-1910 era of segregation then built on. Third, apartheid underwent several substantive systemic changes (with attendant ideological shifts) in the ‘apartheid era’. The starkest occurred in 1990, when South Africa’s formal transition to democracy began.

Apartheid has been described, most usefully, as a form of racial capitalism in which racial differences were formalised and socially pervasive, and society was characterised by a powerful racially defined schism. Greenberg observes:

“[T]o one side, a dominant section with disproportionate control over economic resources, a presumptive privilege in social relations, and a virtual monopoly on access to the state; to the other side, a subordinate section with constrained economic resources and with little standing in social or political relations.”[iii]

When considered against the world’s other racial orders, South Africa was unique, both in terms of its rigidity and the pervasiveness of race, as a social construct. It would clearly be a mistake to view its form of domination as an amorphous, all-encompassing relationship between social groupings distinguished by their physical characteristics. This would omit the complex interplay of identities – ethnic, social, gender, cultural, linguistic, political and, crucially, class – that informed apartheid’s fundamental schism. This understanding clearly informs Greenberg’s assertion that racial domination is best understood as “a series of specific class relations that vary by place over time and that change as a consequence of changing material conditions”.[iv]

There is strong evidence to suggest that in the era before European colonisation of South Africa neither race nor ethnic consciousness shaped identities.[v] Colonial social engineering, focused and energised by the industrialisation of the late nineteenth century, fashioned racialised social groupings. South Africa’s capitalist development in the first half of the twentieth century, founded on the need to accommodate resilient non-capitalist modes of production, fostered the development of ideologies that were informed by the segregation and control of pre-capitalist societies. This was the crucible out of which both Afrikaner and African nationalism emerged.

From the mid-1970s onwards, forces in capitalist development began to undermine South Africa’s framework of racial domination, producing what Stanley Greenberg has called a “crisis of hegemony”.[vi] Rapid population growth and urbanisation were pressurising the apartheid regime, and so was a changing economy, whose growth was beginning to be inhibited by apartheid. Pressures from outside the country began to build up, and the global Anti-Apartheid Movement’s use of sanctions, boycotts and divestments was increasingly effective against the Regime. Resistance by Black South Africans intensified, and mass mobilisation began to gain impetus and bridge ethnic and racial divides. Under the leadership of the ANC (African National Congress) and allied organisations, the considerable energies of African nationalism increasingly began to be channelled into a struggle for a democracy defined by non-racism. The attempts of the State to reform the system were frustrated by the inertia of its racial apparatus.,

By the early 1980s White/Settler unities were crumbling and apartheid, as a legitimising ideology, was no longer tenable. As the State plunged deeper into crisis, it attempted to forge a new alliance of classes that were not organised around racial or ethnic identities but rather around the protection of capitalism (the ‘free enterprise’ system) and the aim of protecting ‘democracy’ from a ‘total onslaught by world communism’.[vii] ‘Total strategy’ now replaced apartheid and, in helping to buttress the apartheid system, entailed the suspension of law, the destabilisation of neighbouring countries and the unleashing of state terror on oppositional groupings: these now became the Regime’s primary instruments of power. It was only when it became clear that they would not stop the system from disintegrating that the Regime committed to engage its opponents with the aim of achieving a negotiated settlement.

In 1986, Mandela initiated ‘talks about talks’ with representatives of the South African state from his prison cell, thereby inaugurating almost a decade of negotiations that would culminate in the formal demise of apartheid. Five years later, he was President of the ANC and was leading the liberation movement through the process of transition processes. And just three years after this, he was President of the country, the holder of a Nobel Peace Prize and a global icon of peacemaking. This is very much the view that contemporary popular discourse, which celebrates him as a peacemaker, negotiator and promoter of reconciliation, has of him. However, this selective (mis)remembering of his life and legacy has not been entirely positive and this is why a younger generation of South Africans now excoriate Mandela for having ‘sold out’ Black South Africans in negotiations with the apartheid state and local and global capital.[viii] This selective (mis)remembering has also impacted global audiences by detaching the image of Mandela from the reality and causing significant dimensions of the struggle against apartheid to be overlooked.

Resistance necessarily took many forms, including mass mobilisation and international solidarity, which I have already identified as critical pillars of struggle. Mandela was the ANC’s volunteer-in-chief for the 1952 Defiance Campaign and in the late 1980s and early 1990s was regarded as the symbolic leader of what was called the ‘Mass Democratic Movement’. In the 1970s and 1980s, as the world’s longest-serving political prisoner, he became the symbol and figurehead of the global Anti-Apartheid Movement.

It is less frequently acknowledged that he played a huge role in the ANC’s first experiments in underground organisation and was, in 1961 and 1962, labelled as ‘The Black Pimpernel’ by media. When armed struggle was initiated in 1962, he trained as a guerrilla and became the first commander of uMkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s armed wing.

There is no blueprint for the successful implementation of decolonisation projects, and there is no single authoritative strategy on offer for those involved in struggles for justice. Mandela’s genius was reflected in his understanding of the apparatus of oppressive power that confronted him, his clear focus on the ultimate objective and his ability to combine a principled commitment with strategic and tactical pragmatism.

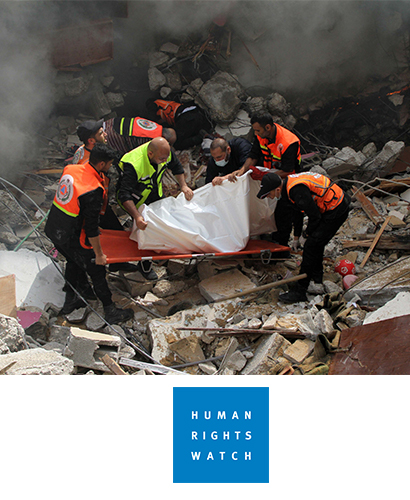

His seminal genius and contribution notwithstanding, South Africa continues to grapple with resilient apartheid patterning, deep-rooted structures of white supremacy and an extractive capitalism. For both South Africa and Palestine the struggle continues (a luta continua).

_________________

[i] Mahmood Mamdani, Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities (Wits University Press, Johannesburg, 2021), pp.20-21.

[ii] The subsequent discussion draws on my essay “The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory and Archives in South Africa”, Archival Science 2,1-2 (2002).

[iii] Stanley Greenberg, Race and State in Capitalist Development: Comparative Perspectives (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1980), p.30.

[iv] Ibid., p. 406.

[v] See, for instance, Carolyn Hamilton and Nessa Leibhammer (eds), Tribing and Untribing the Archive University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, 2016).

[vi] Greenberg, p.398.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Palestinian critics of the Oslo Accords were similarly critical of the compromises that the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) leadership made during the negotiation of the Oslo Accords in the early 1990s. Mamdani, Neither Settler nor Native, pp.308-309.

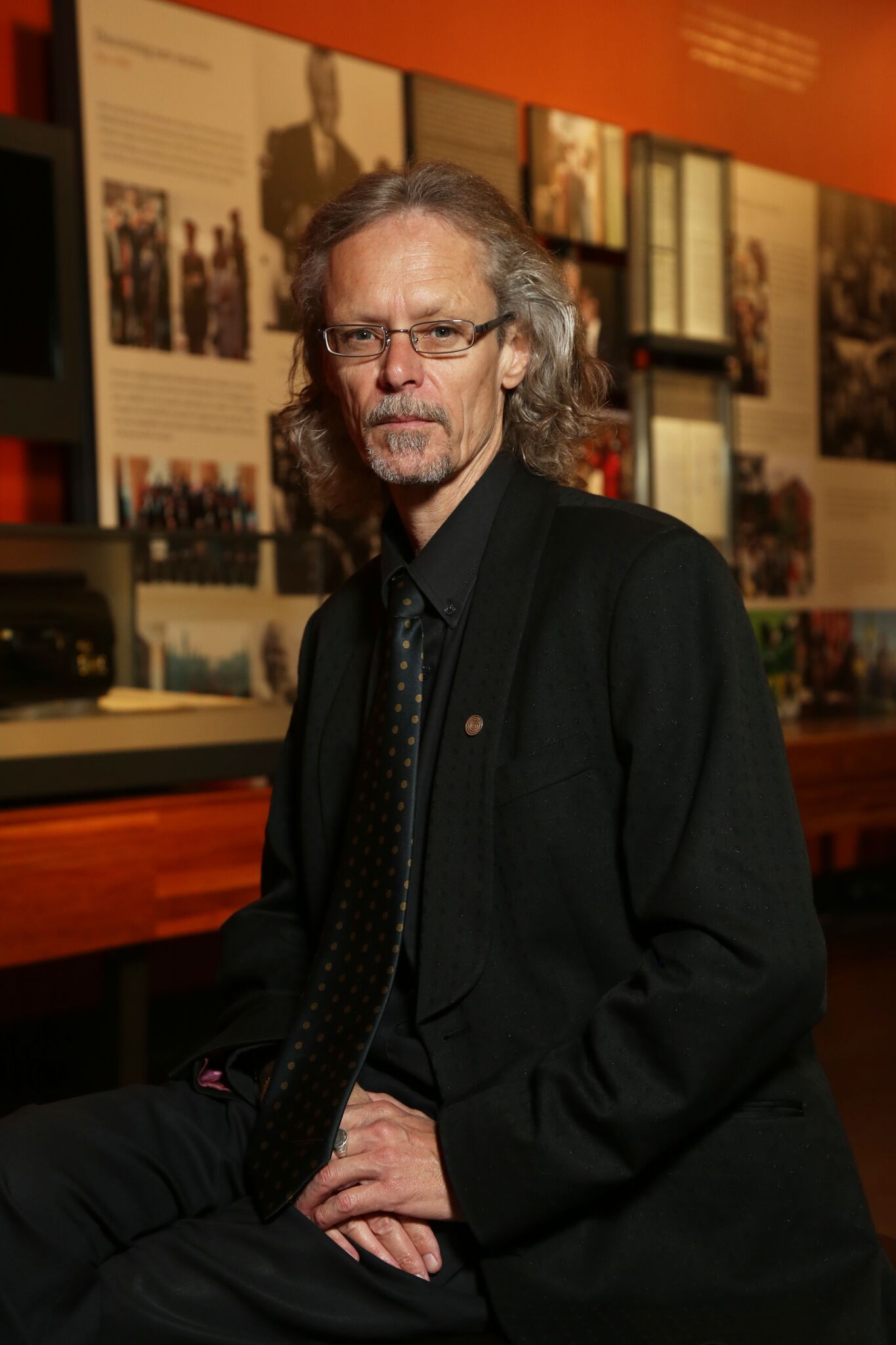

Verne Harris

Verne Harris heads the Nelson Mandela Foundation’s leadership and knowledge development processes. He was Mandela’s archivist from 2004 to 2013, directed the Foundation’s archives programme for 15 years and the dialogue and advocacy programme for 5 years. He is an adjunct professor at the Nelson Mandela University, participated in a range of structures which transformed South Africa’s apartheid archival landscape, including the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and is a former Deputy Director of the National Archives. He has authored or co-authored six books, the most recent one being Ghosts of Archive (2021). He is the recipient of an honorary doctorate from the University of Cordoba in Argentina (2014), held the Follet Chair at Dominican University (Chicago) in 2018-9, received archival publication awards from Australia, Canada and South Africa, and both his novels were short-listed for South Africa’s M-Net Book Prize. He has served on the Boards of Archival Science, the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation, the Freedom of Expression Institute, and the South African History Archive.